New Medicare Rules Tackle Prescription Drug Prices

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 included provisions intended to lower prescription drug costs for Medicare enrollees and slow drug spending by the federal government. According to an estimate by the Congressional Budget Office, the law’s drug pricing reforms could reduce the federal budget deficit by $237 billion over 10 years (2022 to 2031).1

Here’s an overview of the changes to the Medicare program — which covers 64 million seniors and people with disabilities — and timelines for when they take effect.

Drug price negotiation

For the first time, the federal government will negotiate lower prices for some of the highest-cost drugs covered under Medicare Part B and Part D. The first 10 drugs selected for the negotiation program were announced in late August 2023. The negotiated “maximum fair prices” for the initial 10 drugs are to be published by September 1, 2024, and go into effect starting January 1, 2026. Up to 15 drugs will be subject to negotiation each year for 2027 and 2028, and up to 20 more drugs for each year after that.2

Inflation rebates

By one estimate, the list prices of about half of all drugs covered by Medicare between 2019 and 2020 rose faster than inflation.3 To discourage this practice, manufacturers of drugs covered under Medicare Part B and Part D will be required to pay rebates to the federal government if price increases for brand-name drugs without generic or biosimilar competition exceed an inflation-adjusted benchmark (beginning in 2023).

Medicaid, a federal program that provides health coverage for low-income Americans of all ages, already receives similar inflationary rebates.

Redesigned Part D benefits

The new law also modifies the design of Medicare’s benefits and shifts liabilities so that Part D insurance plans will pay a larger share of the program’s drug costs, while enrollees and the government pay less.

Under the 2023 Medicare Part D standard benefit, enrollees pay a $505 deductible and 25% of all drug costs up to the catastrophic threshold, and then a 5% coinsurance (above $11,206 in total costs or $7,400 in out-of-pocket costs). But there is currently no limit on the total amount that beneficiaries might have to pay out of pocket if high-cost drugs are needed.

Starting in 2024, the 5% coinsurance requirement for Part D prescription drugs in the catastrophic phase is eliminated, which effectively caps enrollees’ out-of-pocket drug costs at about $3,250. A hard cap of $2,000 will apply to out-of-pocket costs for Part D prescription drugs in 2025 and beyond (adjusted for inflation). Annual premium increases will also be limited to no more than 6%.4

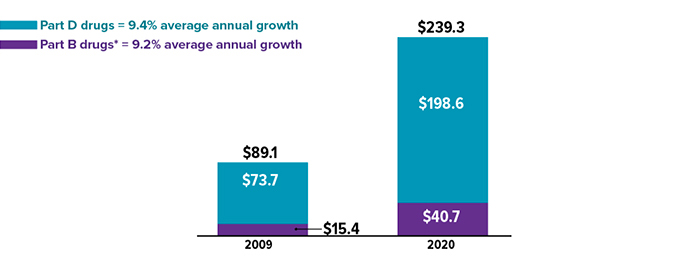

Rising Medicare spending on drugs (in billions) between 2009 and 2020

*Typically administered by a health professional in a hospital or another medical facility. Source: MedPAC Data Book, July 2022

Insulin cost-sharing limits

Starting in 2023, deductibles will not apply to covered insulin products under Medicare Part D or under Part B for insulin furnished through durable medical equipment. Also, the applicable copayment amount for covered insulin products will be capped at $35 for a one-month supply.

Medicare enrollees who live with a chronic disease like diabetes or face any illness that requires treatment with high-cost specialty drugs (such as cancer or multiple sclerosis) could see significant savings in the coming years thanks to these changes. Still, younger individuals who are uninsured or have private insurance plans with high deductibles could continue to feel financial pain from rising drug costs — with one notable exception.

Three major drugmakers have announced deep price cuts of at least 70% for older forms of insulin. These decisions may have been influenced by public backlash, new competition and changing market dynamics, along with the threat of financial penalties soon to be imposed by Medicaid because drug prices were raised faster than the rate of inflation.5